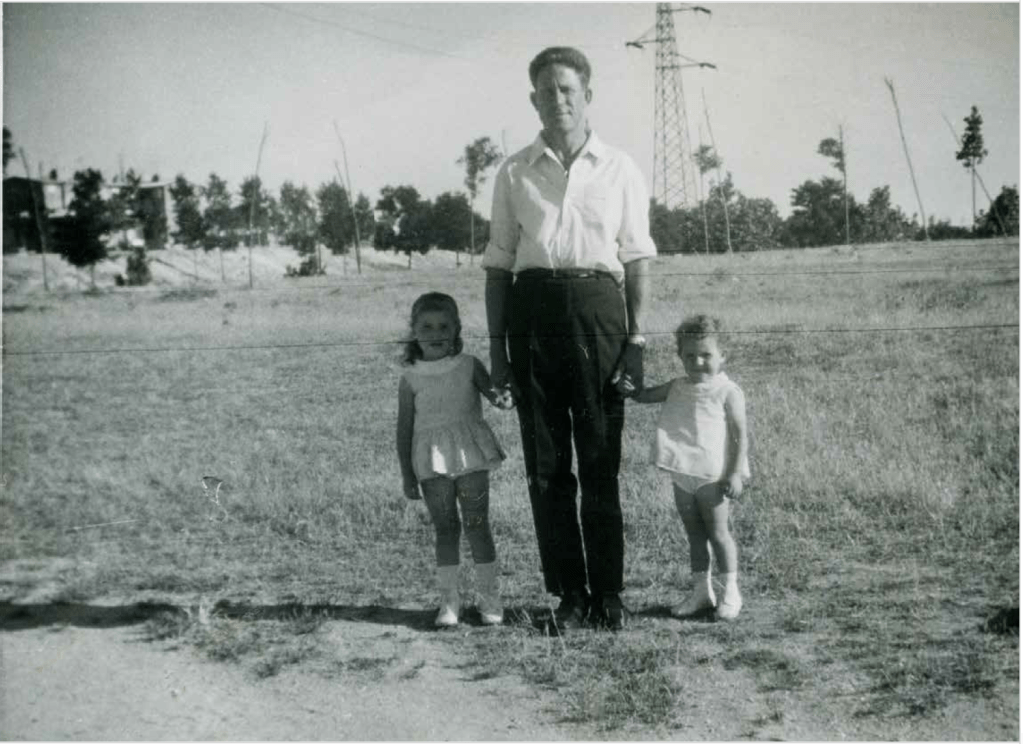

The national migration from the countryside to the city in the 1950s and 1970s, in Spain, as a result of the post-war hunger and repression, resulted in “the city” with its “rings of peripheries” and in the passage from the rowhouse to the apartment. The rise of remote work nomadism and urban tourism, consolidating city centres as “cityless” places, merely reserved for leisure from 2005-2005 has led to a collective shift within the city, from the center to the neighborhood. The periphery, due to the gentrification of the city center, is no longer a dormitory city, it is the city. This new phenomenon overlaps with the natural disappearance of the generation that arrived in these neighborhoods when they were young, grew old in them and that bequeaths their flats to their daughters and sons. Urban and domestic spaces that seemed to define a less brilliant past of the country, are once again the present. Do we still need what our parents did? Are these spaces suitable for the citizens of the 21st century, their lifestyle and their expectations? It is difficult to avoid reflecting on these spaces and their weight in defining the identity as individuals and as a society. There is a need to put back into the collective mentality those apartments in the buildings on the outskirts of the cities where a large part of the current Spanish population was born and raised.

Posing the same questions from the philosophical point of view, this investigation is about a gradual phenomenon of dissolution of the physical: from the open space with the open air to the containment of the apartment in the city or from the country to the balcony (1965-1995) and the fundamental transition from living in the present to living in real time in front of a screen (1995-2025). This dissolution of the physical has changed our perception and relationship with space, as well as the identity of cities, but apartments and neighborhoods remain fundamentally the same

From the Country to the Balcony

PART I – The memory

Chapter 1- Land and Shoes

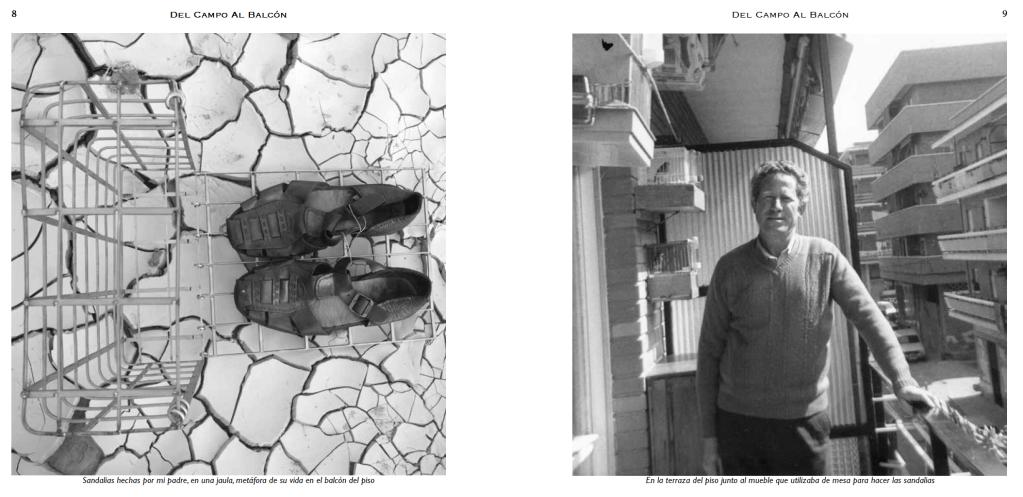

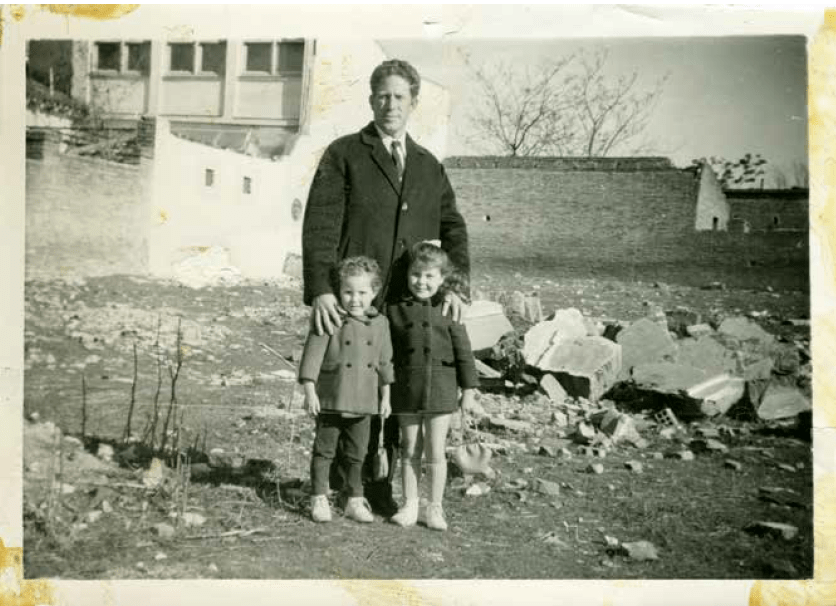

The starting point is the finding, after the death of the author father, of 25 pairs of shoes, made by him and for him. The author asked herself why shoes? And to answer this question traces the story of her family arriving to neighborhood in the periphery of Madrid, the life in a rowhouse, the eviction, the move to an apartment, and how her father maintains his hobby of making shoes, on the 3 feet-wide balcony of his 550 SQF apartment as a way of keeping alive the memory of his land that he left behind when he came to Madrid. This chapter serves as an introduction to rootedness.

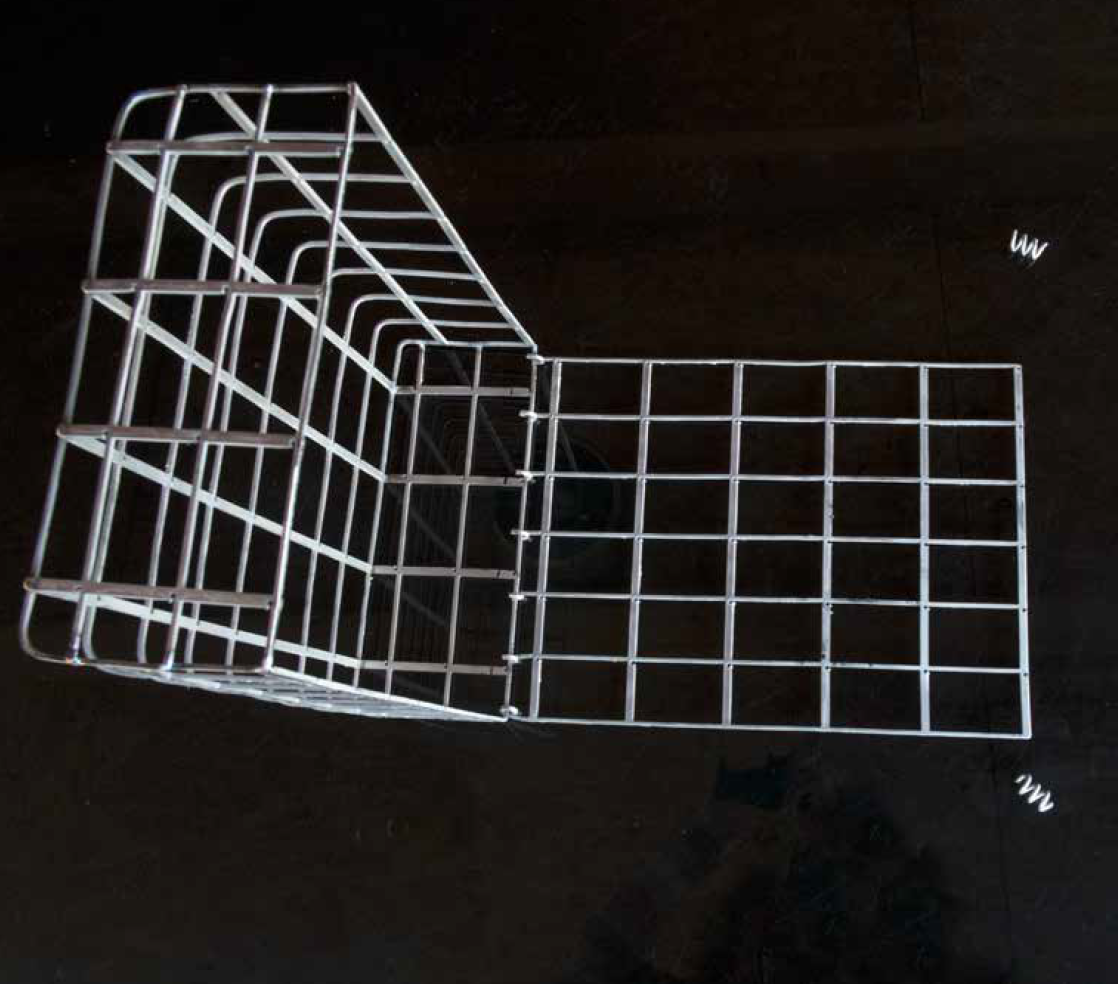

A cell for the shoes, to remain of the containment in which my father expend his life in the balcony of his 550 SQF apartment.

Chapter 2- From the House to the Apartment

The transition from horizontal to vertical housing, from a row house in the city, of poor construction, with licks, without comforts but with a patio, trees, rooftop and a lot of life in common with the neighbors to a residential building on the same lot, without life in community, with almost no space to move in the 550 SQF apartment and in which the open air is reduced to a balcony.

This land is where Madrid Barajas airport of Madrid is now located.

PART II–Preserving collective housing and memories

Chapter 3- The MeToo of housing and neighborhood

Beyond “the right for housing”, a movement of resignification of housing (#ahousenotabox) is needed to reshape and rehabilitate collective housing in the peripheries of the cities.

A movement of recognition of the origins of these homes is important for the reaffirmation of the inhabitants: I am from the countryside, I arrived to the city looking for work but there is no inferiority in rural living, nothing to be ashamed of this or any neighborhood in the periphery.

Ascao, Madrid, Spain.